Maintaining Independence: Widows as Landladies During the Georgian Era

Margaret Rooke Stevenson was born in 1706. She married Addinell Stevenson, a merchant, but he passed away around 1747. 1 Their only daughter, Mary “Polly” Stevenson was born on June 15, 1739. 2 After Addinell died, Margaret and Polly took up residence at 36 Craven Street in 1748. Very little is known about Margaret’s life until Benjamin Franklin began renting four rooms from her in 1757. He was Margaret’s most famous resident. Margaret took to Benjamin quite well, essentially serving as his society wife by attending functions with him and hosting dinners together. 3 Franklin praised her immensely in his letters, even calling her, “…a certain very great lady, the best woman in England….” 4 When Franklin returned to the United States, their relationship remained quite strong.

When Margaret was widowed, she gained a status unlike any other. As is the case with much of history, women during the Georgian era had limited power on their own. Being a widow was the best-case scenario for many as it granted an unmatched level of independence. While what was available to widows was limited by what their husbands left to them, “Widowhood was, to all intents and purposes, the only period in the life of a woman when she was in control of her own destiny: no longer managed by either father or husband.”5 Many widows made money as landladies because “It allowed them to stay in the family home and provide a little company and social life.”6 Though it was not viewed as the most acceptable profession, it was seen as a somewhat respectable way for widows to make money.

The main draw to becoming a landlady was that it allowed women to make a living in a respectable manner in a world that did not want them to have autonomy. According to Amanda Vickery, Mary Pendarves, who was widowed at age 24 said, “‘My fortune…was very mediocre but it was at my own command.’”7 If a woman could make money, she could support herself and be independent. Because widows had been married at one point, they had an additional advantage over spinster who were, “at best a curiosity, and at worst a problem.”8 The respectable independence that could be established by widows as landladies was unmatched.

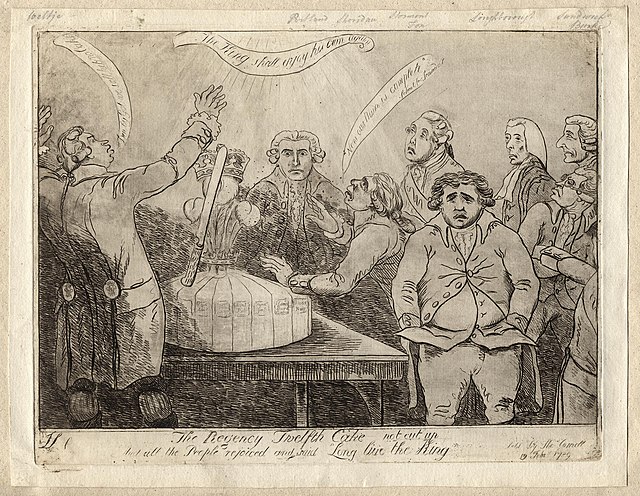

The independence that these women had caused many to be fearful. As a result, there were many stereotypes circulated throughout the media about landladies, one of which was that of landladies as brothel madams or prostitutes. This caricature is portrayed across several different types of media, including many illustrations.9 There is no solid backing to this claim as, “None of these [diaries and journals that belonged to landladies], nor any lodgers whose accounts I have researched to date, mentioned any association between their landladies and the sex trade – even when the landlady was a milliner, the occupation most associated with undercover brothels in novels.”10 A blanket statement cannot be made that there were no instances in which this stereotype was true however, it can be safely assumed that a fair amount of it can be chalked up to a dislike of a woman having autonomy. A common thread throughout history is society being scared of independent women. Having harmful stereotypes against them, such as labeling them objects of sexual desire, would tarnish their reputation and make people afraid of them.

Another assumption made about landladies is that they were nosey. They had the keys to the house and could go about the space as they pleased. The landlady was often the only person with a key to the rooms so she would have been able to traverse the rooms as needed or as she pleased. There was a chance that a lodger would have access to a key for their rooms as well but it was not overly common.11 With the landlady generally being the only person to have the key, it is understandable that people might find them suspicious. In a society that thrived on a patriarchal hierarchy, having a woman in a position of power such as a business owner in the way that the landladies were, would have lead to some uneasiness about what they had the ability to do.

Despite these stereotypes, lodging houses were fairly nice places to live. A common theme across many pieces of research is the creation of a domestic community. Seeing as many landladies were single women, having lodgers to share a common space would have been given them social interaction and a sense of community within their own homes.12 For the lodgers, renting out rooms, “…was also carefree, avoiding responsibility for home maintenance and liability to serve in parish office or pay most taxes.”13 For the most part, rooms on the ground floor were used for visitors while the owner of the house would live on the middle floors. 14 At 36 Craven Street, this was very much the same. On the bottom floor, were Margaret Stevenson’s parlour and a cardroom in which she allowed Franklin to host guests. He rented four rooms within the house and was quite social with Margaret and her daughter Polly.

Becoming a widow and making a living as a landlady was liberating for many women. Widowhood was one of the few ways a woman like Margaret Stevenson could be independent, still maintain some sort of social standing, and continue to be seen as respectable without a husband. Supporting themselves by renting rooms was a simple way to earn money and give themselves a place within society.

By Charlotte Frick