Parties, Cakes & Mistletoe: A Georgian Christmas

“A good conscience is a continual Christmas” – Benjamin Franklin

Read on as we explore the Georgian Christmas practices of holiday cakes, large parties, mistletoe décor, and other beloved Christmas traditions that Benjamin Franklin and the residents of 36 Craven Street likely enjoyed.

How did Benjamin Franklin and the residents of 36 Craven Street celebrate the Christmas season?

After Christmas’s banishment from English society in 1644 by Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell, Christmas did not regain its place as one of the most beloved holidays in English society until the Georgian and Victorian eras. Georgian Christmas was a time of balls, parties, courtship, and family gatherings that stretched from December 6th (St Nicholas Day) to January 6th (Twelfth Night).

English gentry spent their Christmas season in country estates and houses, while the rest of English society enjoyed a day from work as Christmas was a national holiday. Christmas day would be spent at church before indulging in a lavish or hearty Christmas meal full of traditional foods. Typically Christmas meals served goose, turkey, or venison depending on social class and financial status followed by a Christmas pudding, mimicking King George I’s first Christmas dinner which served plum pudding in 1714. Mince Pies would accompany the Christmas meal but, unlike today, these would be semi-savoury and made from ground meat, normally beef or tongue, with sweet currants.

On the 26th, St Stephen’s Day, the staff would have the day off whilst the household would recover from the food and drinks. People would donate to charity and the upper classes would gift their staff Christmas Boxes, which is where the term Boxing Day comes from (first used in the 1830s).

Decorating for Georgian Christmastime

All social classes would decorate their homes with traditional decorations such as evergreens, fruits and ribbons. This was not done until Christmas Eve, however, because it was considered unlucky to decorate before then. Kissing boughs and balls were also popular, usually made from holly, ivy, mistletoe and rosemary and decorated with spices, apples, oranges, candles or ribbons. In very religious households, families did not use mistletoe due to its scandalous connotations!

A cosy fire was an important component of Georgian Christmas. A Yule log, chosen on Christmas Eve and wrapped in hazel twigs was dragged home by horse to burn in the fireplace for the 12 days of Christmas. It would be put out on the first Monday after the Twelfth Night, also called Plough Monday, for good luck in the New Year. A piece of the log would be kept back to light again the following Christmas.

Nowadays, however, most households have chocolate Yule logs rather than wood. We’re not complaining!

Twelfth Night Christmas Celebration

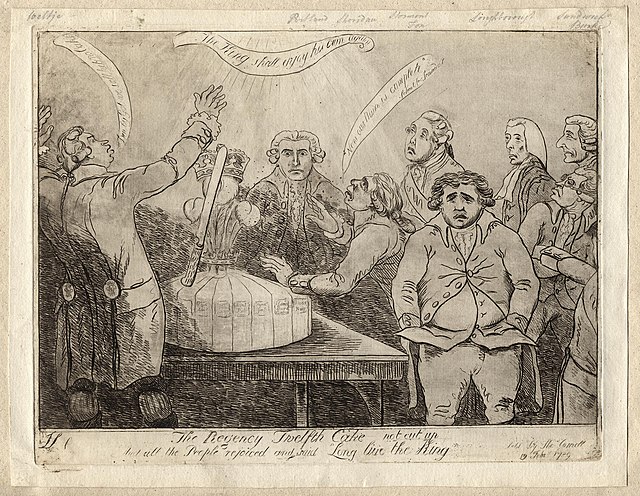

January 6th or Twelfth Night signalled the end of the Christmas season and was celebrated by a Twelfth Night party with party games, dancing, drinking and eating.

The Twelfth Cake, which gave rise to today’s Christmas cake, was the highlight of the party and a slice was given to all members of the household. Traditionally, it contained both a dried bean and a dried pea to elect a man as king for the night, and a woman as queen. In wealthy households, staff would generously also be offered a piece of the Twelfth Cake.

The Twelfth night would also include Wassailing – a hot, mulled punch. Wassailing dates back to the Anglo-Saxon era and has evolved over the years.

There were different types of Wassailing, depending on location and social class. For wealthy households, a Wassail bowl would be passed around guests for everyone to take a sip and toast the next person. From the 1600s, poor households would take a Wassail bowl containing a mulled ale drink known as Lamb’s Wool around the streets. People would be offered a drink in exchange for money. From the late 16th century, Wassailing in some regions would incorporate a visit to an orchard with song and dance underneath the trees to wake them and encourage them to produce a good crop the next year.

After the Twelfth Night celebration, families took down all the decorations and burned all the greenery to avoid bad luck in the New Year. Even today, many people superstitiously take down all their Christmas decorations before 6th January.

Plough Monday (the first Monday after the Twelfth Night) was more commonly celebrated in agricultural areas. Farm labourers would paint their faces black with soot and pull a decorated plough around the more affluent houses in their local villages in exchange for money.

Where’s our month-long holiday?!

The extended Christmas season disappeared after the Regency period by the rise of the Industrial Revolution and the decline of the rural life. Employers needed workers to continue working throughout the holiday season, creating the shortened Christmas period of today. Tragic.

To learn more about Georgian Christmas here at Craven Street, join our free, Virtual Talk: Christmas at Craven Street on Wednesday 14 December 2022 – 5pm GMT/12pm ET!